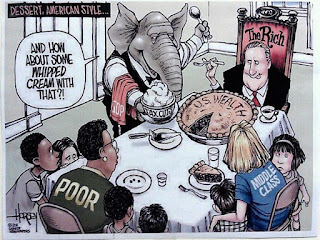

We Can No Longer Afford To Remain Silent About Growing Inequality.

In Volume 1, Chapter 26 (The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation), of Capital, Karl Marx describes how the more closely society corresponds to a deregulated, free-market economy, the more the lop-sidedness of power between those who own the means of production and those who labor under them will produce an "accumulation of wealth on one pole" and an "accumulation of misery, agony of toil, slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole."

This was not idle speculation on Marx's part; history has proven him correct.

You don't believe me? Well, look at the data.

The nation's poverty rate: according to data released earlier this month by the US Census Bureau, about 2.5 million Americans slid into poverty last year. The number of people living below the poverty line (46.2 million) is the highest number ever reported in the 52 years the bureau has been publishing poverty statistics.

The official poverty rate, however, does not fully capture the breadth and depth of poverty in America. To put it bluntly, the way in which we measure poverty is ridiculous, dramatically underestimating the extent to which people are experiencing social and economic hardship. The official poverty line in 2010 for a family of four was $22,314. Few families anywhere in the country live comfortably on such a paltry income.

Not surprisingly, the poverty rate is worse for people of color. According to the bureau, the poverty rate for blacks rose to 27 percent, up from 25 percent in 2009, and, the Latino poverty rate stood at 26 percent, up from 25 percent the year before. By comparison, the white poverty rate was 9.9 percent, up slightly from the 2009 rate of 9.4 percent.

The nation's unemployment rate: The poverty rate is climbing, in part, because of the high unemployment rate that has gripped the nation since the start of the Great Recession. Overall, the unemployment rate stands at 9.1 percent, which has left roughly 14 million Americans out of work. If you include people who have given up on their search for a job out of frustration and the people who prefer full-time work but have only been able to find part-time work, about 15 percent of all Americans (roughly 25 million people) have an employment problem.

Joblessness has hit people of color particularly hard. The unemployment rate for Latinos is about 11.3 percent and about 15.9 percent for Blacks (which leads the nation).

Growing wealth inequality: Household wealth – the accumulated sum of assets (houses, cars, savings and checking accounts, stocks and mutual funds, retirement accounts, etc) minus the sum of debt (mortgages, auto loans, credit card debt, etc.) – is a far better measure of inequality than income.

Although it's a global phenomenon, in the U.S., over the last three decades, the super rich have been piling up fortunes at an astonishing rate. In 2007, the people at the top of the income distribution, the top 1 percent of earners, took home a whopping 18.3 percent of national income. In 1973, their share was only 7.7 percent – in a little over thirty years, the super rich increased their portion of national income by more than two and a half times. "Richie Rich" hasn't lived this good since 1929.

Once again, not surprisingly, some groups have been hit harder than others by growing inequality. An analysis of data recently released by the U.S. Census Bureau shows a widening racial and ethnic wealth gap. Based on data from 2009, according to the Pew Research Center, the median wealth of white households ($113,149) is 20 times that of black households ($5,677) and 18 times that of Latino households ($6,325). This is the largest wealth gap ever found since the government began publishing such data more than 25 years ago.

The reason for the "lopsided wealth ratio," write the authors of the Pew report, is because "the bursting of the housing market bubble in 2006 and the recession that followed from late 2007 to mid-2009 took a far greater toll on the wealth of minorities than whites."

Amazingly, the Pew analysis also shows that roughly 1 out of 3 black (35 percent) and Latino (31 percent) households had zero or negative wealth in 2009, compared to only 15 percent of white households.

In a new report, Private Transfers, Race, and Wealth, the Urban Institute examines the relationship between private transfers (financial support received and given from extended families and friends, as well as large gifts and inheritances) and the racial and ethnic wealth gap. They conclude that blacks and Latinos receive less private transfers than whites – especially in the form of large gifts and inheritances. According to their analysis, inter vivos and intergenerational transfers of wealth account for about 12 percent of the racial gap in wealth between blacks and whites.

So, where is the anger?

Where is the outrage?

Why are people so silent about growing inequality?

Why the silence?: One reason for the silence is that most Americans don't envy the rich; we drink the Kool-Aid. While the gap between the rich and the poor in the US is larger than in any other advanced capitalist society, most people want to join the "super" rich rather than see wealth spread more evenly across society.

And, in spite of the evidence showing that social mobility has grown increasingly difficult for most people, Americans cling stubbornly to the belief that if they work harder than the next guy, there is a pot of gold sitting at the end of the rainbow.

There was a time not long ago – the first couple of decades following World War II – when the U.S. economy expanded and American workers saw their wages and quality of living rise dramatically. But, since the early 1970s, the wages of most workers have failed to keep pace with inflation.

The impact of stagnant wages, however, was dulled by rising house prices and easy access to credit. When they didn't find their pot of gold, the middle class used home equity loans and credit card debt to make the dream "seem" real.

Another reason for the silence is because most people believe that poverty is not caused by capitalism and that people are poor simply because they are less able and less talented. Hence, most people, especially the rich, have no interest in ending poverty and have resigned themselves to the idea that inequality is never going to go away because some people deserve to be poor.

We can no longer afford to remain silent about growing inequality. Changing our way of thinking will not be easy. The widespread embrace of the benefits to be gained from individualism and the financial rewards that capitalism provides the highly skilled and highly educated, along with the acceptance of personal responsibility for one's own well-being together constitute a formidable ideological barrier to the kind of collective action needed to confront poverty and inequality.

Nonetheless, the truth is that the fundamental forces shaping global capitalism today – jobs ranging from manufacturing to clerical work can be done more cheaply and more profitably by machines and low-wage workers in developing countries – are hostile to the middle class dream that defined our nation during much of the second half of the 20th Century.

It's time to let our voices be heard.

Comments

Here's the more interesting question: What do we do about it? You say that we "can no longer afford to be silent about growing inequality." Well, what should we say about it? The conditions that allowed the creation of middle class America, namely the availability of moderately skilled jobs in commerce and manufacturing, no longer exist. It is unfair to complain about income inequality without pointing to the nonsustainability of the American economy as the root cause.

And now I return to my initial reaction: what should we do about it? Should the federal government tax the rich more to balance out their rising income? Should the government provide jobs or additional income to the poor? How can the federal government move the American economy beyond its failing 1950s model and into the 21st century? And if it can do any of these things, should it?

Political analysis only gets interesting when you add in some controversial political theory. At least, that's when it gets interesting to me.